Artificial intelligence is no longer a distant curiosity in Africa — it’s a priority. From Addis Ababa to Accra, governments, regulators and industry players are racing to turn AI’s promise into practical gains for economies and societies while trying to avoid the well-known pitfalls: bias, surveillance, job disruption and data colonialism. What makes the current moment distinctive is that African policymakers are pursuing three things at once: coordinated continental strategy, ambitious national roadmaps, and a pragmatic response to extra-regional rules like the EU’s AI Act. The result is messy, creative, and, crucially, consequential.

A continental framework with local flavors

In May 2025 the African Union elevated AI to a continental strategic priority — a signal that African states intend to approach AI not as isolated projects but as a collective development agenda emphasizing investment, inclusion and home-grown governance. The AU’s move frames AI as part of industrialization and digital transformation across member states and sets a timeline for coordination and capacity building.

That continental signal matters because many African countries lack the institutional depth to regulate complex emerging technologies on their own. The AU strategy aims to provide shared principles — on data governance, ethics, and skills — while allowing national governments to tailor rules to local conditions. This hybrid approach recognizes one hard truth: Africa is too diverse for a single one-size-fits-all legal regime, but too connected (cross-border data flows, regional markets) for wholly independent regulation.

National strategies are moving from aspiration to implementation

A striking trend in 2024–2025 is the shift from policy talk to concrete national strategies. Kenya released a National AI Strategy for 2025–2030 that maps public-sector adoption, research incentives, and ethical frameworks designed for its economy and regional role. The strategy signals Nairobi’s intent to be a policy leader — not just a market — on the continent.

Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy by population, has been advancing its own National AI Strategy and regulatory drafts. The government’s documents emphasize harnessing AI for public service delivery, local innovation ecosystems, and a commitment to safeguarding privacy and consumer rights as the technology scales. These drafts also reflect an awareness that AI policy must link closely with data protection, industrial policy and skills development.

Put simply: national governments are waking up to AI as a strategic lever for competitiveness — and are trying to avoid the twin traps of over-prescription (which stifles startups) and laissez-faire (which invites abuse and external dependency).

The EU AI Act and data geopolitics: external rules, internal consequences

African policymakers are watching extra-regional regulation closely, particularly the EU AI Act, which entered into force in 2024 and is being phased in through 2026–2027. The Act’s rules on high-risk systems, provenance, and prohibited practices are already influencing how African regulators think about risk categories, vendor accountability and cross-border data flows. For African firms that sell into Europe or rely on European cloud services, compliance is not optional — it shapes product design and market access.

This dynamic raises a policy dilemma: should African countries adopt EU-style rules, adapt them, or chart an independent path? Many experts argue for “regulatory subsidiarity” — borrow technical standards that protect citizens while preserving policy space for industrial policy and local innovation. Copy-paste regulation risks either importing mismatched rules or perpetuating dependence on foreign legal templates; participatory lawmaking that includes informal sector actors is the alternative.

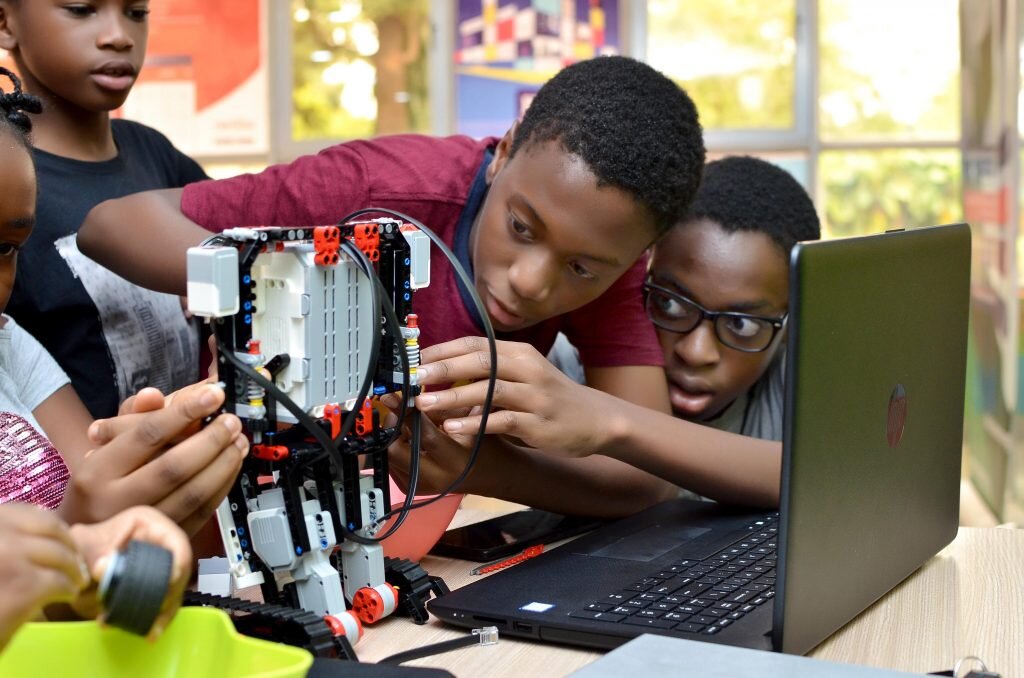

Skills, infrastructure and the private sector: the capacity struggle

Policy is necessary but not sufficient. Implementation requires data infrastructure, skilled talent, and computing capacity. That’s why global partnerships and industry programs — for example Microsoft’s commitment to train large cohorts in AI and cybersecurity — are part of the story. These programs can accelerate capacity building, but they also raise questions about whether skills pipelines will feed local firms or simply make talent more portable for multinational employers.

At the same time, the “state of AI in Africa” assessments show rapid ecosystem growth in research hubs, startups and applied projects (health, agriculture, finance) — yet they also document gaps in datasets, testing facilities, and robust evaluation frameworks that regulators need to assess risk and impact.

Key tensions and policy priorities

Across documents and debates, five tensions recur and should shape policymaking:

1. Protection vs. Innovation — How to regulate high-risk uses (e.g., biometric surveillance) without smothering entrepreneurship.

2. Local datasets vs. privacy — Encouraging local data collection to avoid algorithmic bias, while protecting citizens’ rights.

3. Harmonization vs. sovereignty — Building regional standards that enable markets without eroding national policy choices.

4. Skill creation vs. brain drain — Training talent at scale while keeping incentives for home-grown companies.

5. Global rules vs. digital colonialism — Avoiding a future where external standards determine African digital infrastructure and value capture.

Practical recommendations for African policymakers

Policymakers who want to turn strategy into results should prioritize three pragmatic steps:

Invest in data commons and interoperable standards. Publicly funded, well-governed datasets for health, agriculture and transport can lower barriers to locally relevant AI and reduce dependence on foreign data providers.

Adopt tiered regulation. Use risk-based rules that are strict for surveillance and predictive policing but proportionate for developer tools and low-risk applications.

Scale skills through public-private partnerships. Combine formal education reforms with industry certifications and micro-credentialing tied to real projects — with clauses that encourage local employment and entrepreneurship.

Conclusion: an uneven but hopeful road ahead

Africa’s AI policy landscape in 2025 looks less like a single roadmap and more like an archipelago of experiments — continental principles, national strategies, corporate training programs and external regulatory pressures. That complexity is a strength if policymakers use coordination to share standards, invest in common goods, and insist that AI governance support African industrial goals rather than outsource them.

The continent’s choice is stark: treat AI as a lever for inclusive transformation, or allow it to become a vector of external control and domestic harm. The early signs — AU strategy, Kenya and Nigeria’s blueprints, growing civil society research — suggest many African actors are choosing ambition with caution. The job now is to translate strategy into enforceable, equitable practice.